Whether you’re writing a novel, a screenplay, graphic novel or other kind of story, writing a scene that engages your reader from start to finish is crucial.

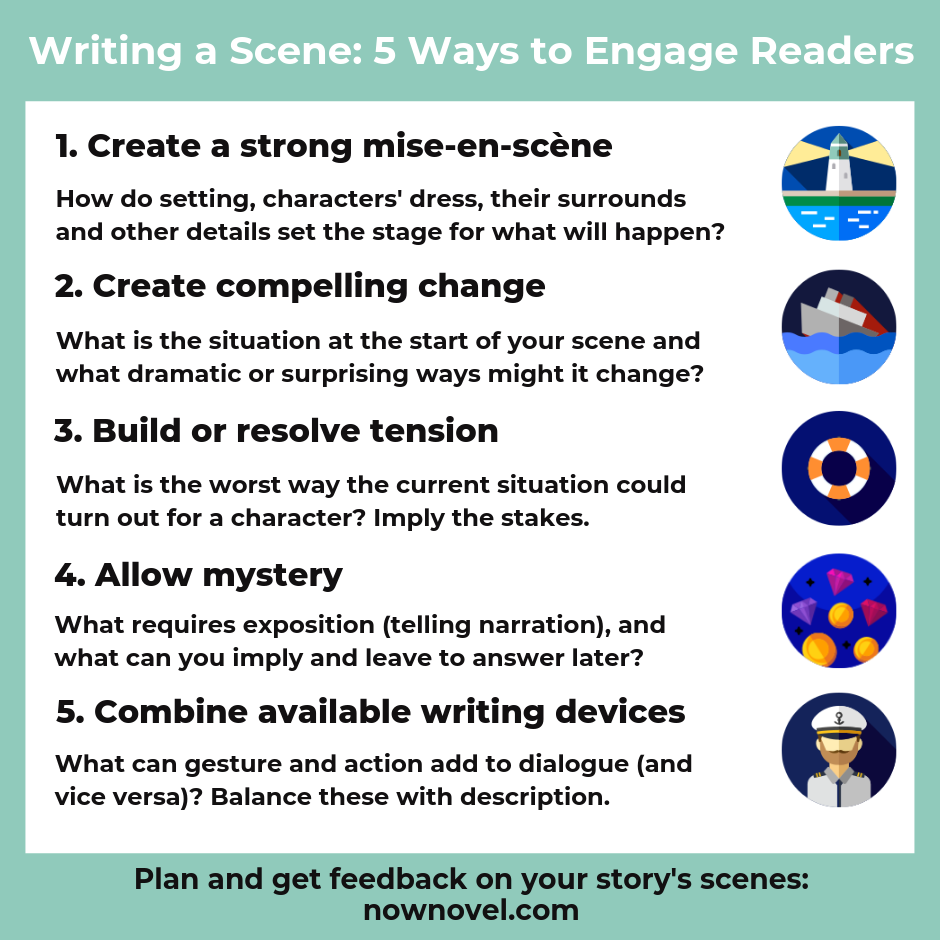

Try these 5 tactics to keep scenes engaging:

1. Make your mise-en-scène interesting

Mise en scène is a French term from film and theatre meaning ‘the arrangement of everything that appears in the framing – actors, lighting, décor, props, costume’.

It’s useful to think of written story scenes visually, too, as if you can’t see characters’ world, chances are your readers won’t, either.

Example of effective mise-en-scène in a story

In Alice Munro’s short story ‘Soon’ from her collection Runaway (2005), she describes a character, Penelope, catching a train to her birth town, many years later:

She got off in a town twenty miles or so away from the town where she had grown up, and where Sam and Sara still lived. Apparently the train did not stop there anymore.

She was disappointed to get off at this unfamiliar station and not to see reappear, at once, the trees and sidewalks and houses she remembered – then, very soon, her own house, Sam and Sara’s house, spacious but plain, no doubt with its same blistered and shabby white paint, behind its bountiful soft-maple tree.

Alice Munro, ‘Soon’, Runaway (2005), p. 89

Munro’s collection of scene details, the sights Penelope sees (and the absent ones she expects but doesn’t see), convey the effects of returning to a place fixed a certain way in your memory. The way Munro positions Penelope stepping off the platform in relation to her surroundings draws us into the scene.

The above example shows a second major element of interest in any scene: change.

2. Create compelling change

In writing a scene, think about plot (as well as setting) as situations plus change. What does your character want? What changes must (or happen to) take place en route to this goal? How does a setting change over time? What do these changes tell us about a place’s history?

A great scene often will bring us from one state of uncertainty (a character nervously preparing for a date, for example) to another (the same character waiting for their date to show up). Change often requires braving the unknown.

Even in a story where everything seems to stay the same (for example, in Samuel Beckett’s famous play Waiting for Godot two tramps wait endlessly for a mysterious figure who never arrives), something changes. In Godot, a ragtag assortment of secondary characters who are not Godot arrive, this delaying the main expected arrival.

Beckett’s play is an example of how change plus surprise (whether pleasing or upsetting in nature) together create interest.

Example of scene-writing illustrating change

Changing characters’ behaviour towards each other in a scene based on new information they have gained makes characters’ relationships dynamic and interesting. [Outline characters and their motivations and plan scenes in Now Novel’s story dashboard].

Consider this example from Kent Haruf’s Our Souls at Night (2015). A shopkeeper knows an elderly lady, Addie, has been having sleepovers with another elderly man. Addie’s friend Ruth/Mrs Joyce defends her against the clerk’s judgment:

Did you find everything, Mrs. Joyce? Everything you wanted?

I didn’t find me a good man. I didn’t see one of them on the shelf. No, I couldn’t find any good man back there.

Couldn’t you? Well, sometimes they’re closer to home than you think. She glanced quickly at Addie standing next to the old lady.

How much is it? Ruth said.

The clerk told her.

Your blouse has a spot on it, Ruth said. It’s not clean. You shouldn’t come to work dressed like that.Kent Haruf, Our Souls at Night (2015), p. 33

[Ed’s note: Haruf himself does not use speech marks for dialogue throughout the book].

This brief interaction shows how the rumor mill has changed the clerk’s attitude towards Addie. It also shows Ruth’s loyalty in her defense of Addie against the clerk’s subtle commentary .

It creates an immediate sense of how public gossip changes Addie’s relationship with various other town locals.

The above example of interesting change in a scene leads us to another key element of interest: Tension.

3. Build or resolve tension

Tension in a scene is a product of uncertainty and the resulting suspense we feel.

To take the analogy of watching a tightrope walker, we know they are moving from an A to B of safe ground. Yet between these two points, how things turn out depends on many variables. Their balance, focus and how they place their feet. And how swiftly they correct any stumble.

Sometimes in a scene, this metaphorical tightrope is between skyscrapers – the balancing act seems an insane risk. Other times, it’s just a zip-line between two trees in a park. The tension is minimal, but the walker (your character) is still mesmerizing to watch.

How do you build tension in a scene?

We create story tension by showing or implying uncertainties and conflicts:

- Introduce uncertainties with stakes: What is the worst case scenario if your character takes a misstep? Do they have a safety net? (How high are the stakes?)

- Bring in conflict: Is your character struggling with themselves, other characters, their environment, or even (like Addie in the example from Kent Haruf above) their society?

The exchange between Addie, Ruth and the store clerk in the example above is a good example of how even small tensions make scenes crackle with dynamic uncertainty.

Ruth mentions not finding a man on the shelves as a light-hearted joke, yet the clerk takes this comment to personal insinuation with their indirect comment about Addie. In this moment, a boundary is crossed, bringing out Ruth’s fighting spirit.

When it feels a scene is lacking tension, ask:

- What could go wrong now, and how would characters react based on what we know about them so far?

- What boundaries are there between characters, or in a situation, and what happens if they are crossed?

Resolving the tension in a scene also creates interest. When two friends who have fallen out make up, there’s still tension until the conflict is fully resolved. Waning tension still produces suspense as we know any attempt at resolution could still veer off course.

4. Allow mystery

Often in beginners’ writing, a scene loses the spark of interest because the writer takes pains to explain every single detail. To give a simple example, compare the following two descriptions of an injury:

Effective scene-writing: Too much telling versus allowing mystery

She was running too fast down the steps, delighted school was out for the week, when she tripped and broke her leg clean through. How am I going to make hockey practice this weekend? was all she could think. There was a big game the following week.

Every single incident in this sequence of action is explained, both in its immediate effects and in the possible impact it will have.

Now consider a more mysterious alternative:

She hurtled down the steps the second the early Friday bell rang. Finally! I can’t wait for practice tomo- She gave a surprised shout as she fell. Moments later, as she lay dazed, a blinding pain began to throb along her shin. This can’t happen now! The game’s next week…

In the second example, there is implication. It being weekend is indicated by the ring of the bell. We know the character has practice, but not the object of said practice. There’s reference to ‘a game’ yet we have to wait to learn what sort of game this is.

These small mysteries make the action and its outcome itself more compelling. There is movement and engagement in the scene, rather than the remove of a narrating voice telling us every detail. We get to live the scene as the character experiences it, from their viewpoint.

Both kinds of narration have their place. The first is more heavy-handed with exposition, while the second shows and implies context, leaving in more blanks for the reader to fill in later.

Allowing this sense of mystery – events to knit together like a crossword puzzle – gives readers the pleasure of suspense, great and small.

5. Vary the writing devices available to you

The wonderful thing about writing is there are so many literary devices at our disposal. We have language games like simile and metaphor (saying one thing is like another, or making them equivalent). We have dialogue – characters’ voices and vocabularies – and action. Narration and description, too.

Example combining writing devices

In Toni Morrison’s novel Jazz (1993), she balances characters actions, descriptions and dialogue beautifully. Consider this example, where cosmetics salesman Joe wants to make a proposition to a character named Malvonne who wants to mail a letter:

“No.” He held up his hand and walked past her into the living room. “I’m not selling. See? I don’t even have my case with me.”

“Oh, well, then.” Malvonne followed him to the sofa. “Have a seat.”

“But if I was,” he said, “what would you like? If you had a nickel, I mean.”

“That purple soap was kind of nice.”

“You got it!”Toni Morrison, Jazz (1993), pp. 44-45

See how Morrison combines gesture (Joe holding up his empty hand to show he doesn’t have a selling agenda and inviting himself in) with dialogue. Later in the scene, Morrison shows Malvonne looking at her mantel clock mid-dialogue to show she has a pressing agenda of her own:

“What brings this on? You ain’t selling you giving away free for what reason?” Malvonne looked at the clock on the mantel, figuring out how much time she had to talk to Joe and get her letters mailed before leaving for work.

Morrison, Jazz, p. 45

Here, characters words show what they intend to say while small actions and gestures – Joe’s barging in, Malvonne’s glances at the clock – show their unspoken additional character traits and desires. Together, dialogue and action reveal small differences between open and private wants and intentions, adding layers of characterization. These details together create an interesting scene where we’re aware of people’s competing desires.

What do you think are the elements of a good scene?

Join Now Novel and get constructive peer feedback or guidance from a writing coach in developing your scenes into a compelling story.

4 replies on “Writing a scene that engages your reader: 5 tactics”

I think a good scene also plants seeds for what’s to come, especially in mystery where we go back and think…Ahhh! I remember when he said or she did that…how could I have missed that?!

Even outside of clues, a good scene can help set up the next and build anticipation.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts, 2Cents 🙂

That’s true, so many strong scenes start with an intriguing mystery (even a simple opening line like ‘Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself’ in Mrs Dalloway may be mysterious, too, as we think ‘why *herself*?’ and ‘what flowers? For what occasion?’). So there can be intriguing mystery in even mundane actions. That’s the set up you refer to.

Thanks for reading, keep writing!

Mmmm. Mystery in the mundane. Indeed.

[…] Source and read more: https://www.nownovel.com/blog/writing-a-scene-that-engages/ […]